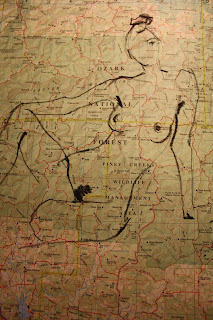

There's a dreamy, delicate whimsy to the surreal pencil-and-watercolour world of Marianna Marx. It has been delighting regulars to Melbourne design markets like Rose Street, the Queen Vic Night Market, Fed Square's Markit and the Northcote Town Hall's Kris Kringle Night Market for the past few years and has earned her representation at Signed and Numbered print gallery alongside high profile names like Miso, Ghostpatrol and Tai Snaith. Most importantly, however, it has been entertaining the quietly spoken artist herself for as long as she can remember.

Marianna grew up in Camberwell in Melbourne's eastern suburbs drawing whatever popped into her head on whatever she could get her hands on – a habit she retains to this day. She was hooked on drawing as a kid and vividly recalls filling her first sketchbook – a gift in early primary school that came with a particularly exciting set of watercolours.

"I was probably in Prep, I think, so about five years old, and I remember going through a whole sketchbook in a couple of days just having so much fun using way too much water," Marianna recalls. "All the pages got soaked. I've always had sketchbooks for as long as I can remember. I've got piles and piles at my parents' house up in the attic."

Pencil and watercolour firmed up as her medium of choice early on but she has experimented widely with sketchbook styles, road-testing various formats, sizes and paper types. "I don't think I've got one type of sketchbook," she says. "When I was doing art at school there was a lot of pressure that ... each page should be beautiful in the sketchbook and really well ordered and showing your trial and error very clearly. And I just found that so fake. I found those sketchbooks just completely contrived. I have sketchbooks all the time, but a lot of my sketches are just on whatever piece of paper I have with me at the time."

Post It notes, maths homework, bills or shopping lists have always worked just as well for capturing her ideas in the moment as beautiful moleskin journals or thick, creamy watercolour paper. "Sometimes some of the best drawings come out when it's just a piece of paper that has no real value to you, or monetary value either," she says. In preparation for our interview Marianna's mum produced a whole box of doodled treasures retrieved over the years from the desk in her home office. "When I was living at home she said that every single time she'd go to her desk there'd be like a Post It note I'd scribbled on, the back of all her bills would be scribbled on, because I'd sit on the phone and draw," Marianna says.

After high school Marianna studied Visual Arts at Monash, followed by a Diploma in Illustration at Chisholm. She has been illustrating professionally for about four years, since holding her first market stall and launching her website. "I guess that's when I first started to think about making money from my artwork, with the goal of being able to do this as my full-time career," she says. "But I did it really gradually. I just did a market here and there and had my online store. I just kept refining it – and still am refining it, how to best present my work."

Setting aside time to sketch is central to her practice. She keeps a pencil, jar, fine brushes and a portable set of watercolours with her to ensure she can capture ideas when they come to her – while watching fashionistas stroll around Rose Street, for example, or while one of the young art students she tutors is busy working on an observational drawing. The crucial thing is not the type of book or surface she uses but the act of creative play itself. Spontaneous sketching is "the one place where you can play", according to Marianna. "And I think you're really limiting yourself if you trying to make each page look like a presentable piece of art," she says. "Sometimes that does still creep in but then I just think, 'This is for no one else but me'."

"I've been listening to a few podcasts lately about creativity and a lot of them are staying that that's the place that creativity comes from, a place of complete play and willingness to make mistakes."

Unlike artists who regularly trawl through their sketchbooks looking for images that still resonate and seem to demand further development, Marianna rarely leafs through the pages of old sketchbooks. Important images tend to return to her spontaneously. "Today when I was looking through all these sketchbooks I was like, 'Oh, I want to draw that and that and that idea, so it might be something to put into practice," she says with a laugh. "But unless they kind of come back to me ... naturally I don't like the idea of going back to a drawing because I really do think they were reflective of that period in time or that part of my life. I want to just stay in the present, and I feel like I've maybe got out whatever I needed to draw then and so I don't really need to do it again."

But when an idea she has sketched – sometimes years before – appears again and again in her mind's eye, she knows it's a lead worth following. The rudimentary pencil sketch of a winged girl (above) inspired the recently completed illustration (below), but Marianna had forgotten the sketch existed until she began toying with themes she couldn't seem to shake. "I remember always wanting to do something with these wings made out of twigs that a girl has tied together," she says. "I was wanting them to look like she's made them. And then I was thinking about this idea of puzzles and piecing things together and solving your own problems, and that (old) image popped back into mind."

The carefree playfulness of sketching often captures more than just fertile themes, and is starting to change the way she approaches finished artwork. "I often find that the sketches and sketchbook will ... really capture the gesture and the spontaneity and looseness of what I'm trying to express so much more than when I go to do the final artwork," Marianna says. "And so a lot of the time now I'm just trying to capture those spontaneous, loose lines (and) I've started drawing directly onto the 'nice' paper. It is completely not economical, at all, but I'll try and just draw straight onto there and kind of pretend I'm drawing in my sketchbook even though it's a three dollar piece of paper," she says with a laugh.

Like most of us Marianna, admits she struggles to find time for creative play the busier she gets, but it's something she's prioritising at present. "It's definitely a work in progress," she says. "It's hard sometimes when you've only got an hour and you need to finish something to think, 'Oh I'm just going to experiment'. But I think it's vital in challenging yourself and in progressing. Sometimes I feel a bit stuck and I think it's because of a lack of play. The times it's best for me to play are when I've set the time aside for it so I'm really relaxed and calm and just trying to be open to whatever comes."

Ideas often emerge in the precise colours she'll use in the final artwork, but their timing is utterly random. Marianna loves drawing from nature and often finds herself sketching in parks and on beaches little botanical studies that later weave their way into her work. Observational studies of human figures are a constant too, and prove their worth when she's later trying to nail particular stances or gestures in imaginary characters. Generally, though, she prefers to sketch in private. "I've always wanted to be one of those artists that could sit in a cafe and observe people," Marianna she says. "But I always feel really shy doing that, and really kind of exposed. So I tend to do it either at night before I fall asleep, or in my studio, or my room."

Marianna's illustrations are populated by solitary figures or adventurous pairs, often dwarfed by fantastical surroundings or preoccupied with surreal endeavours. Deceptively simple, strangely elusive vignettes are packed with recurring themes like bare trees and autumn leaves that are rich in personal symbolism for the artist. For the viewer, who can only guess at the layers of meaning underlying each piece, it's ripe territory for the imagination.

Images from nature inspire Marianna with their beauty, but also offer "a way of telling little stories", she says. "The ideas themselves, the actual concepts, I think come from so many different things. They're usually quite personal things like a conversation I've had with someone. They might not look all that expressive or emotional but I see a direct relationship between whatever's happening in my life at that moment in time and the drawings I do. I think there's a lot of personal symbolism.

For Marianna, sketching is about capturing thoughts visually "before your brain can interject too much". Allowing time for these thoughts to percolate through her subconscious and morph into a story with personal resonance is vital for her work as an illustrator. "Sometimes I get a bit impatient and it's really ... not beneficial to your work because you might rush an idea before it's had that percolating time," she says. "If you can just sit with it for a while it will be so much better and it will come out so much more naturally than trying to force it." A story will emerge from life, a day dream, a song lyric or a series of images that she can't shake, which will eventually transform her initial thought into a fully formed narrative – of sorts. Marianna is careful not to stitch up her stories so tightly there's no room for viewers to interpret them through the lens of their own experiences and associations. "I kind of like the idea of leaving it really open with no setting or background so that hopefully other people can read into it with their own stories and kind of attach their own experiences," she says.